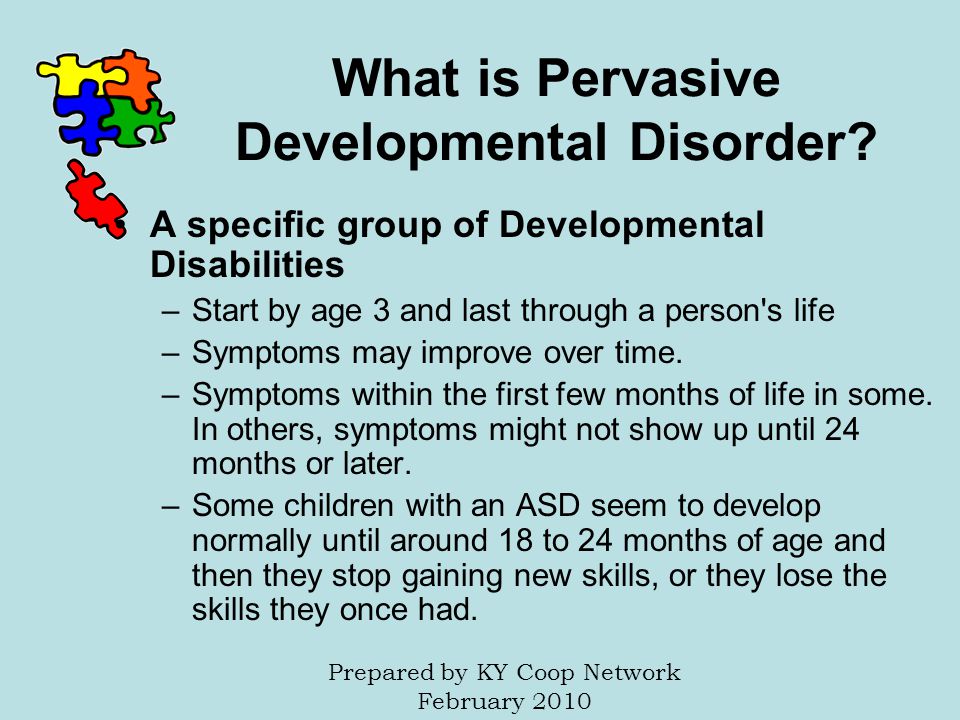

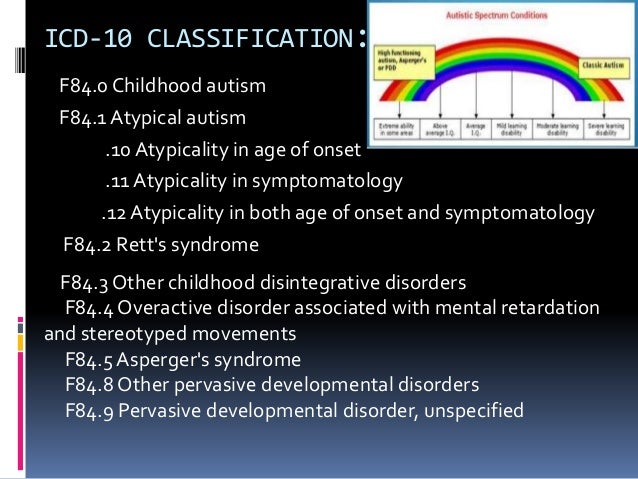

High-functioning pervasive developmental disorder (HFPDD), also known as Asperger’s syndrome, is an autistic spectrum condition characterised by “qualitative abnormalities of reciprocal social interaction that typify autism, together with a restricted, stereotyped, repetitive repertoire of interests and activities”. We have surveyed all residents of Sheffield aged 13 and over who may have or are known to have an ASD but do not have an intellectual disability, and we consider here estimates of the demand for diagnosis, for treatment of comorbid psychiatric disorder, and for social care based on our findings. How big a demand will this be? Are colleagues right to fear that they will be inundated, as some do? Inevitably some people who were diagnosed as children may want the diagnosis to be reviewed and may also turn to the community mental health team for services or advice. If that were so, then 0.3% of adults with no intellectual disability would have an ASD and any of them who have not previously had a diagnosis might turn to the community mental health team for a diagnostic assessment. It is commonly assumed that these prevalence figures, which have all been based on surveys of children, also apply to adults. This rise in reported prevalence has been much greater in those without an intellectual disability, who now account for about half of those with a diagnosis of an ASD. Team members may be reluctant to accept responsibility for adults with an ASD but no learning difficulty considering the rising prevalence of children identified with an ASD over the last decade, with prevalence estimates currently reaching those of schizophrenia, that is, 1% of the population (Baird et al.). Community mental health teams are hard pressed in the UK and everywhere in the developed world. Trainee psychiatrists and clinical psychologists have been expected to be familiar with the criteria for the diagnosis of autism for years (unpublished correspondence to the second author from the board of examiners of the UK Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the British Psychological Society), but people seeking a diagnosis of ASD are regularly turned away from mental health teams because they lack training.Ĭommunity mental health teams may also argue that they are not commissioned to provide diagnosis or management, but this is likely to change once the strategy is implemented.

Responsibility for the diagnosis of people with an ASD who do not have an intellectual disability is much less clear, although a recent report of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in the UK indicated that it can best be carried out by community mental health teams, not least because many adults with an ASD seeking diagnosis may have a comorbid psychiatric disorder. The “second strand of the strategy” is to develop a “clear, consistent pathway for diagnosis of autism.” The strategy also calls for estimates of the numbers of adults with autism.Ĭurrently the diagnosis and management of adults with an autism spectrum disorder (an ASD) in combination with an intellectual disability is the responsibility of learning disability teams, who have considerable, and well-established, experience.

The UK Government has recently (March 2010) published a strategy for adults with autism (Fulfilling and rewarding lives) building on the Autism Act of 2009, and the National Audit Office report Supporting people with autism through adulthood. This raises the possibility that AS symptoms might become subclinical in adulthood in a proportion of people with HFPDD. Another contributory factor might be that the prevalence of high-functioning pervasive development disorder may decline with age. We suggest several explanations for the findings, including reduced willingness to participate in a study as people get older, increased ascertainment in younger people, and increased mortality. The results of this study are preliminary and need follow-up investigation in larger studies. in the over 60s (1 person in every 38500 in this age group). in the group aged 13 to 14 years old (1 young adult in every 900 in this age group) to 0.

of the population of Sheffield city aged 13 or over, but the prevalence by year of age fell from a maximum of 1. The detected prevalence of possible or definite HFPDD was found to be 0.

112 possible and definite cases were found, of whom 65 (57%) had a previous diagnosis. A survey was undertaken to investigate the prevalence of high-functioning pervasive developmental disorder (HFPDD) in a community sample of teenagers and adults aged 13 and above in the city of Sheffield, UK.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)